Welcome to my latest blog post. Recently, I have been discussing the Ancient Greeks and Romans. Specifically, their beliefs surrounding disabled people and their abilities. It is clear that disabled people were not deemed to be useless. While I would love to go on and on about various ancient civilisations for a long time, I won’t. I feel that would discriminate against other time periods and we wouldn’t want that, would we? With that in mind, I shall launch myself into the period known as the Middle Ages. I have not found it as easy as I thought to find relevant information, but I will start by looking at Bede and his work.

Who was Bede?

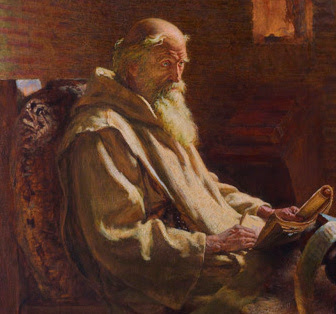

Bede, also known as Bede the Venerable, was a monk from what is now England. He was born in 672/673 CE in the Kingdom of Northumbria. As well as being a monk, he was a fruitful writer of history. He spent a large portion of his life writing. Was it an interesting life? I think that depends on what you deem to be an interesting life. Much of the evidence about Bede’s life comes from what he tells us in his writings. Some historians have speculated that Bede may have been part of a noble family in that region. They point out that the name Beda (The Old English for Bede) can be found in the list of kings for the Kingdom of Lindsey, which was next to Northumbria. This link to high society through birth may explain how he was connected to all the right people when it came to gathering knowledge for his works.

He states that he was born on the grounds of the monastery at Jarrow, where he lived his entire life. However, it is more likely that he was sent there at the age of possibly 7 or 9, so that his family could have a member in the clergy. He really did stay in Jarrow for the rest of his life. Obviously, travel in the 7th and 8th century was very different to what it is now. Historians have only found concrete evidence of Bede leaving Jarrow twice in his lifetime. Once to Lindisfarne, an island roughly 100 kilometres away. While the other was to York, roughly 130 kilometres away. So, what did he spend his time doing? Well, writing mostly. He wrote the Ecclesiastical History of the English People which I will discuss in a moment. As a result, he is sometimes remembered as the ‘Father of English History’. He is also credited with popularising the use of AD to denote any year after the birth of Christ. So whilst he was fairly stationary throughout his life, you cannot say he wasn’t productive!

The Ecclesiastical History and Disability

You might be wondering what Bede has to do with disability. As he wrote so extensively and was so influential, Bede’s works may indicate what Medieval attitudes towards disability were, particularly within the church. The Ecclesiastical History for which he is best known contains various references to disabled people. It was written in Latin in the year 721. I think I will pick my favourite examples and use them to emphasise my point. Wait! What is my point? I’m sure I will remember it.

Anyway, there once was a man named Germanus, who severely damaged his foot in a snare. Unable to bare weight, he was stuck in his house. The neighbouring building caught fire and the flames quickly encircled Germanus. The villagers tried to fight the fire to save him, but every part they attacked intensified instead. However, through the power of prayer alone, Germanus was able to quench the flames. Not only this, but a short while later an angel appeared and healed his foot completely. You see, a strong belief in God cured him of his impairment!

There is a similar story which I also enjoy. Two bishops headed out to convert the English to Christianity. They encountered a king named Elafius, who had a disabled son (his leg was bent out of shape). Elafius is preached to and blessed before they heal his son. All of his people gather around to watch the miraculous healing. They are so in awe of what they see that they all become Christian. I think it is safe to assume that the son’s deformity was a metaphor for the wickedness of the pagan English. This in a roundabout way suggests that disability was equated to sin and faith was the only way to avoid it.

I know I’ve only discussed a small percentage of one man’s work, but I think it sums up Medieval attitudes to disability quite well.

To keep up to date with my latest blog posts, you can like my Facebook page, or follow me on Twitter. You can find them by clicking the relevant icons in the sidebar.

Next time I will be discussing the idea of monsters and monstrosities.

The Wheelchair Historian

Further Reading

BBC, ‘The Venerable Bede (673 AD - 735 AD)’, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/bede_st.shtml Accessed: 30th January, 2021.

Bede, Maura Bailey, Autumn Battista, Ashley Corliss, Eammon Gosselin, Rebecca Laughlin, Sara Moller, Shayne Simahk, Taylor Specker, Alyssa Stanton, Kellyn Welch, and Kisha G. Tracy. "Physical Disability, Muteness, Pregnancy, Possession, and Alcoholism from Ecclesiastical History (ca. 731)." In Medieval Disability Sourcebook: Western Europe, edited by McNabb Cameron Hunt, 345-64. Punctum Books, 2020. Accessed: January 18, 2021. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11hptcd.33.

British Library, ‘Bede’, https://www.bl.uk/people/bede# Accessed: 30th January, 2021.

Fiorentino, Wesley, ‘Bede’, published on 10 May 2017 https://www.ancient.eu/Bede/ Accessed: 30th January, 2021.

Wilde, Robert, ‘The Venerable Bede’, Updated May 30, 2019 https://www.thoughtco.com/the-venerable-bede-1222001 Accessed: 30th January, 2021.