|

Welcome to the latest post in my series on disability as entertainment. This week I will be discussing the history of freak shows, with a particular emphasis on the 19th century version. This of course was the era of P.T. Barnum, who, in recent years has been brought back into the public's mind, through the musical movie The Greatest Showman. You may be disappointed, but not surprised to hear that the reality of the situation was no song and dance. As you can imagine, the topic of freak shows is gargantuan. There are already several books written on the topic, and with a growing interest in disability history, there is bound to be several more. With that in mind, I have decided to divide this topic across several posts. This first one will give an overview of what freak shows were, as well as a brief timeline of their popularity. The subsequent posts will focus on particular people and performers involved in the industry.

As with pretty much every topic I cover, this post includes a term which is no longer deemed acceptable when discussing disability. This week that word is freak. If you would like to know why I use derogatory terms, you can read my post ‘The History of Disability Terminology’.

Freak Show: Origins

Okay. I have yet to explain what a freak show actually was. Basically, a group of people who had an unusual appearance, or who could perform unusual acts were put on display and the public would pay a fee to see them. I am well aware that freak shows still take place today, but I am using the past tense, as this is a history blog after all. The freak show was a culmination of several aspects of disability history, that I have already discussed, or will be discussing on this blog. For instance, ‘monstrous’ births have been documented as far back as Stone Age cave paintings. In Ancient Egypt, there were dwarf gods (e.g. Bes), as well as dwarf jesters. Throughout history, there has been a fascination with abnormal bodies. I suppose the 19th century freak shows could be seen as the peak of this interest.

What became the freak show, had its origins in 16th and 17th century Europe. Before this time, the physically deformed were feared as they were seen as bad omens. However, this belief faded, and the public wished to learn more about these people. ‘Monster shows’ took place in taverns, coffeehouses, marketplaces and fairs throughout Europe. Instead of freaks, the performers were known as ‘human curiosities’. These shows made their way to the USA in the first half of the 18th century. It was here that freak shows took off.

The Peak of the Freak

The freak show was at its most popular during the 19th century in America. This was in large part thanks to the work of P.T. Barnum. He was excellent at promoting his shows and making people believe in his tales, no matter how farfetched they were. For instance, his very first attraction was Joice Heth, an elderly African American woman in 1835. Barnum displayed her as being the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington. People were completely convinced by this story, that even when she died and doctors revealed her to be only 80 years old, people still believed in Barnum. He went from strength to strength, accumulating a retinue of curiosities and toured America.

The most famous of these performers was General Tom Thumb, whose real name was Charles Stratton. Barnum encountered Stratton when he was just 4 years old. Given Stratton’s short stature, Barnum was able to pass him off as 11 years old. I feel Stratton is an important example when discussing the history of freak shows. I assume that bringing a small child around the world and making them perform for the public’s amusement is against the law today. The way the freak show performers had to display themselves must have been degrading, right? However, this was not necessarily the case. Stratton was a gifted performer, who could do impersonations, as well as other acts. He was as famous for his abilities, as his disabilities. The freak show performers were also incredibly well paid, earning the equivalent of modern-day sports stars. Stratton died incredibly wealthy, leaving a widow behind and he was not the only one to do so. Look, I’m not saying the freak shows were a good thing, I’m just pointing out that freak show performers did not necessarily live bad lives.

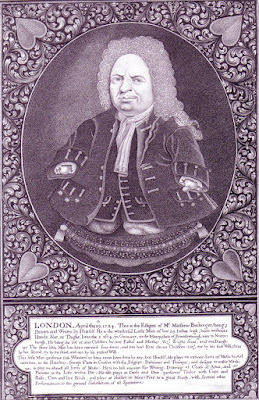

|

| Charles Stratton Aged 10 |

The Decline

While freak shows and their performers were popular in the 19th century, this popularity rapidly declined during the 20th century. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, there was the progression of scientific knowledge. Where once a creative showman could whip up an elaborate tale to explain the bizarre ‘monster’ you saw before you, doctors could now identify many of the illnesses or defects which caused the deformity. This removed the wonder for most spectators. The First World War had a massive role to play, which makes sense when you think about it. You would no longer find deformities entertaining after so many soldiers had been disfigured by the conflict. The freak show, as popularised by P.T. Barnum, virtually ceased to exist by the 1940s. This was also caused by a growth in other forms of entertainment, such as radio and cinema. Furthermore, as you might have guessed, when the disability rights movement emerged in the latter half of the century, they were not best pleased with disabled people being put on display for profit. Finally, with increased supports for disabled people, such as the welfare state in Britain, there was no longer a monetary need to join a freak show.

As I mentioned earlier, freak shows still exist today. However, there is a big difference between them and their 19th century counterpart. The majority of the performers today are self-made freaks, meaning that they have purposefully changed their appearance of their own free will. The freak show performers of the 19th century had far fewer options.

To keep up to date with my latest blog posts, you can like my Facebook page, or follow me on Twitter. You can find them by clicking the relevant icons in the sidebar.

Next week I will be doing a special blog post to mark Halloween. In the meantime, I’m off to watch The Greatest Showman for the 100th time.

The Wheelchair Historian

Further Reading

Bogdan, Robert, Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit (Chicago, 1990).

Chemers, Michael M., Tesch, Noah, ‘Freak show’, Nov 05, 2014 https://www.britannica.com/art/freak-show Accessed: 23 October 2020.

Cleall, Esme, ‘Missing Links: The Victorian Freak Show’ Published in History Today Volume 69 Issue 2 February 2019 https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/missing-links-victorian-freak-show Accessed: 23 October 2020.

Crockett, Zachary, ‘The Rise and Fall of Circus Freakshows’ https://priceonomics.com/the-rise-and-fall-of-circus-freakshows/ Accessed: 23 October 2020.

National Fairground and Circus Archive, ‘History of Freak Shows’, https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/nfca/researchandarticles/freakshows Accessed: 23 October 2020.

PŮTOVÁ, BARBORA. “FREAK SHOWS. OTHERNESS OF THE HUMAN BODY AS A FORM OF PUBLIC PRESENTATION.” Anthropologie (1962-), vol. 56, no. 2, 2018, pp. 91–102. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26476304. Accessed 23 Oct. 2020.