|

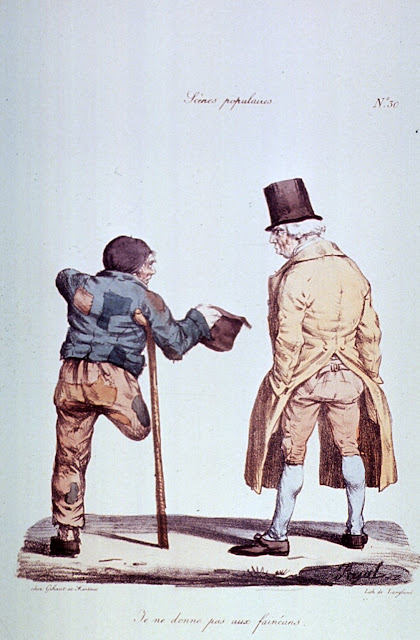

| By Montarde - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16936276 |

As I showed in my previous post, the Roman Emperor Claudius had several impairments which would be considered disabilities today. However, did they negatively impact on his daily life and his role as emperor? This is what I hope to find out.

Attitude of Family

It is fair to say that Claudius’ family were not his biggest fans. On top of his mother calling him “a monster of a man”, his grandmother Augusta hated him and refused to speak to him directly. Instead, she would send messengers, or short harsh letters. Charming! Furthermore, when his sister Livilla discovered that he would become emperor, ‘she openly and loudly prayed that the Roman people might be spared so cruel and undeserved a fortune’. Whether his disability was wholly responsible for these reactions is hard to say. It at least had some role to play.

Caesar Augustus was the step-grandfather of Claudius (It’s a very complicated family tree). Augustus did not hate Claudius, but he certainly did not like him. He was concerned with upholding the family image and therefore attempted to keep Claudius’ condition concealed. This is apparent when he reached manhood. Instead of the regular ceremony, ‘he was taken in a litter to the Capitol about midnight without the usual escort’. It was important to keep his disability hidden as the people of Rome were known for mocking disability. In a letter to his wife, Augustus states

‘we must not furnish the means of ridiculing both him and us to a public which is wont to scoff at and deride such things. Surely we shall always be in a stew, if we deliberate about each separate occasion and do not make up our minds in advance whether we think he can hold public offices or not’.

It could be argued that he pitied Claudius and wanted to protect him as best he could.

Cowering Like a Girl

|

| Detail from the painting A Roman Emperor 41AD by Lawrence Alma-Tadema [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons |

There are several aspects of Claudius’ time as emperor which were seen as negatives. The first grievance that people had was the way that he came to power. His predecessor Caligula was assassinated by members of the Praetorian Guard on 24 January, 41 C.E. He had not been a particularly good ruler and many people wanted him dead. The Praetorian Guard then headed to the palace to kill Caligula’s family. It was here that they discovered Claudius cowering on a balcony (the way any strong leader should). Gratus, the guardsman who found him, proclaimed him to be ‘the new ‘Caesar’ and the new ‘Augustus’’. The Praetorian Guard most likely chose Claudius because he was weak. He also appeared to be a coward. They probably thought that the military would have greater power with such a feeble emperor. As he was put into power by way of a military coup, many believed that Claudius did not deserve to rule. From the very moment Claudius gained power, he was fighting an uphill battle. To maintain control, he removed political opponents and diluted the power of the Senate, gaining the reputation of being a ruthless killer.

Good Aspects of His Rule

There are a couple of incidents which show Claudius’ reign in a good light. These mostly relate to how he dealt with the peripheries of his empire. The first of these is the annexation of Britain. The Romans first established their presence on the island of Britain in 55 B.C.E. with the invasion of Julius Caesar. However, almost a century had passed by the time Claudius conquered the area in 43 C.E. It is impressive that Claudius was able to achieve this feat, especially considering Augustus, who felt that he would amount to nothing, did not. A second good aspect of his rule is a letter from Claudius addressing tensions in Egypt. There had been an ‘outbreak of violence between the Jewish and Greek populations’ of Alexandria. In his response Claudius criticises both the Jews and the Gentiles. This would suggest that he was a strong ruler.

While it is blatantly obvious that Claudius was disliked and openly mocked, this may not have been due to his disability. Even if it was, he managed to stay in power and rule effectively. Overall, his impairment did not negatively impact him.

Next week I will continue my disabled historical figures series by examining Richard III’s alleged deformities.

The Wheelchair Historian

Further Reading

Idris Bell, Harold, 1924. Jews and Christians in Egypt: the Jewish troubles in Alexandria and the Athanasian controversy (British Museum).

Levick, Barbara, 2015. Claudius, 2nd edition (1st edition 1990) (London: Taylor and Francis). Accessed through ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/trinitycollege/detail.action?docID=2046490

Momigliano, Arnaldo, (1934). Claudius, the emperor, and his achievement, Translated by W.D. Hogarth (Oxford).

Osgood, Josiah, 2011. Claudius Caesar: Image and Power in the Early Roman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Scullard, Howard Hayes, 2013. From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome 133 BC to AD 68, reprinted fifth edition (1982; first published 1959) (London and New York: Routledge).

Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars, Claudius, Translated by J.C. Rolfe (January 1914). http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Suetonius/12Caesars/Claudius*.html Accessed: 14 August 2020.