Welcome to my latest blog post. Last week I discussed the

idea of monstrous births, focusing on 16th Century Europe. This week

I will continue along the same line of thought. However, instead of looking at

the disabled children, I will be discussing their mothers. You may remember

from my post on Joseph

Merrick, A.K.A. “The Elephant Man”, that his mother thought she knew what

caused his deformities. She was frightened by an elephant while pregnant and

concluded that this caused her unborn child to resemble an elephant. This

belief which is the subject of this post was known as maternal

impression/imagination.

It’s Always the Woman’s Fault

Let’s see… how do I discuss how babies are brought into this world without going into unnecessarily graphic detail? Em…. when a man and a woman love each other… long story short, the woman becomes pregnant. It is their job to carry the baby inside them until birth. For a long time, (even up to the end of the 19th Century), it was believed that mothers were accountable for the birth defects of their children. It was thought that men had very little to do with the process and the baby was essentially a bun in an oven. That’s right! I just compared pregnant women to ovens. Anyway, to continue my bun in the oven metaphor, if something goes wrong with the oven, you’re not going to have perfectly formed buns!

It was believed that pregnant women had a strong emotional connection with their baby. As in, if the woman was happy, the baby would be happy, if the mother was sad, the baby would be sad. Most importantly, if the mother was traumatised, the baby was also traumatised. So much so, that the traumatic event would imprint itself on the unborn child’s body. An event could impact the child in various ways. Joseph Merrick is an extreme example as his mother was almost crushed by a stampeding elephant. However, there are also less severe examples. For instance, if a woman was eating strawberries when the shock occurred, a red strawberry shaped mark may be left on the child’s body. If the women brought their hand to their face in terror, the resulting mark might appear on the baby’s face. Basically, pregnant women were thought to be able to mould the shape of their baby through their actions and emotions.

Tale as Old as Time

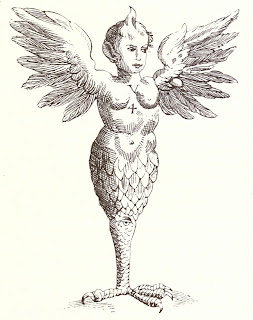

While the idea of maternal impression reached its peak between the 16th and 18th centuries, the concept had been around for a very long time. The ancient Greek physician Galen (born 129 CE) was a believer of this theory. He thought that if a pregnant woman looked at an image of someone, the child may resemble that person. This did not only produce monsters, however. Women were encouraged to gaze at beautiful statues (such as the one above. I think it's beautiful anyway), so that they might produce beautiful children.

This did not always go to plan though. You see, maternal impression could strike at ANY moment from conception to birth. The ancient Greek novel, Aethiopica by Heliodorus of Emesa, contains a perfect example of this. The character Chariclea is revealed to have been born in Ethiopia. As Chariclea had white skin, her mother was afraid she would be accused of adultery and rejected her. We are then told that the mother had been staring at a painting of the white Andromeda in her bedroom and this resulted in the change of skin colour. In later periods similar stories also occurred. For instance, a woman might give birth to a bearded child if they spent too much time admiring an image of Jesus!

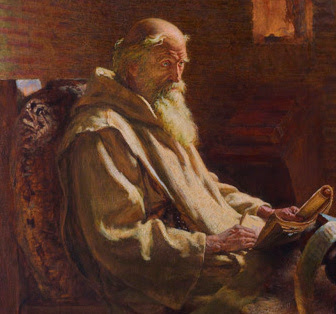

The concepts of monstrous births and maternal impressions fascinated physicians for centuries. A famous example of this is the work of the Frenchman, Ambroise Paré (born c. 1510). In On Monsters and Marvels, he tries to use a scientific approach to explain and categorise monsters and monstrous births. While it may seem strange to us now, he viewed monsters as being as real as any other illness. I find his work fascinating and may go into more depth on it in a separate post.

A much later work on the concepts of monstrous births and maternal impression is by Scottish physician, John William Ballantyne. He wrote the suitably titled Teratogenesis: an inquiry into the causes of monstrosities. History of the theories of the past, in the 1890s. As you can probably tell from the title, he goes into great detail about how the ideas of the past were horribly wrong and modern science had all the answers. I had planned on focusing on his work this week, but then I remembered how long and sciency (that’s not a word) it is!

As you can see, up until fairly recently, women received most of the blame if their child was born with a deformity.

To keep up to date with my latest blog posts, you can like my Facebook page, or follow me on Twitter. You can find them by clicking the relevant icons in the sidebar.

Next time, I will continue my series on monsters by looking at the link between disability and witchcraft!

The Wheelchair Historian

Further Reading

Ballantyne, J. W. (John William), Teratogenesis An Inquiry Into The Causes Of Monstrosities (Edinburgh, 1897) https://archive.org/details/b21981000 Accessed: 12th February 2021.

Lee, R. J. “Maternal Impressions.” The British Medical Journal, vol. 1, no. 736, 1875, pp. 167–169. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25240414. Accessed 2 Feb. 2021.

Snyder, Sharon L.. "Maternal imagination". Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/science/maternal-imagination Accessed 12 February 2021.

The Open University, ‘The theory of maternal impression’, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=65962§ion=1.5 Accessed 12 February 2021.