Welcome to my latest blog post on disability as entertainment. Following on from last weeks post on disability in the Roman arena, I will be examining what life was like for disabled Roman slaves. Well technically, they weren’t actually Roman citizens as they were slaves, but that is just a minor detail.

Romans preferred Cripples?

It is a well-known fact that Roman citizens owned slaves. As bizarre as it seems to us today, possessing slaves was perfectly normal and even expected in Ancient Rome. This ranged from a typical household having one or two, to wealthier Romans having a Downtown Abbey style army of servants. The Romans were so effective at enslaving others, that some have estimated that slaves outnumbered freemen three to one. Understandably, the Roman elite were always worried about slave revolts. This may be one of the reasons why the Romans preferred disabled slaves. It was probably easier to escape an attacker with one leg, for instance.

Deformed slaves were a common sight in Rome. This is due in part to the fact that slaves undertook intensive labour and were often put in dangerous situations, resulting in injury. However, this is not the only way Romans acquired deformed slaves. Quintilian, a Roman educator, and rhetorician stated that ‘some people set a higher value on human bodies which are crippled or somehow deformed than on those which have lost none of the blessing of normality’. It is clear from this that disabled slaves were a sought-after commodity. So much so, that Plutarch records the existence of a ‘monster-market’ in the city. He describes all of the weird and wonderful things that could be purchased there. These include people ‘who have no calves, or are waeselarmed, or have three eyes, or ostrich-heads’. Now, I don’t know about you, but I don’t think I have ever come across a person with an ostrich head. It seems a tad bit unrealistic, but fascinating, nonetheless. These ‘Commingled’ shapes and ‘misformed’ prodigies as Plutarch calls them, were put on display to be gawked at and examined by the public.

It was not only people with pre-existing deformities that were popular with the Romans. Some people even disfigured their slaves to increase their value. I know what you are probably thinking, why on earth would disfiguring someone increase their value? To answer that question, we have to leave reality and enter the realm of the supernatural [insert spooky ghost noises here]. As with most things in daily Roman life, the gods and spirits played a key role. The Romans believed in the Evil Eye of Envy. It was thought that this could have serious effects on the person the Eye set its gaze on. In order to combat this, the Romans used deformed people. The deformity acted to draw the attention of the Eye, thus protecting the original target. The hump on a hunchback was deemed to be the most effective at this. Hence why hunchbacks were commonplace in the imperial court. So, there you have it, instead of using Evil Eye necklaces and bracelets, which is common today, Romans used disabled people!!

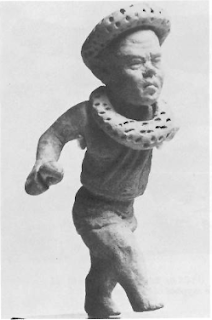

|

| Terracotta dancing dwarf, late 3rd century B.C.E., Rhode Island School of Design, Museum. Providence, Rhode Island. Garland (1995) figure 6. |

Dwarf Clowns

Dwarfs were popular entertainers in Rome and not only as gladiators as I mentioned last week. Usually, dwarf slaves would be made to perform if their master had guests over. This could take the form of singing, or dancing, or just making a fool out of themselves. In short, they were clowns. The satirist Lucian tells of an incident involving such a clown named Satyrion. Satyrion ‘danced, doubling himself up and twisting himself about to cut a more ridiculous figure’. He was clearly intending to make his master’s guests laugh. After this, ‘he began to poke fun at the guests’. Unfortunately for Satyrion, one of them, named Alcidamas, took offence and challenged him to a fight. Being a slave, Satyrion could not refuse and therefore the fight began. Lucian remarks how ‘It was delicious to see a philosopher squaring off at a clown, and giving and receiving blows in turn’. The difference in height certainly would have made an interesting spectacle. The fact that Satyrion actually won the fight makes the event even funnier for those that witnessed it.

Satyrion is not the only example of when a deformed slave was humiliated for entertainment purposes. The Historia Augusta, which is a collection of biographies of the Roman emperors, includes a misdeed of Commodus (yes him again). In my last post, I mentioned how he caved in the skulls of some cripples with a club. This time he was said to have ‘displayed two misshapen hunchbacks on a silver platter after smearing them with mustard, and then straightway advanced and enriched them’. It makes it seem as though the hunchbacks were just a plaything. At least he paid them. That’s a positive, I suppose. Stories such as this indicate that owners of disabled slaves received the most from them, by humiliating them for entertainment.

As you can see, disabled slaves in Ancient Rome were highly prized possessions, but they were humiliated for entertainment.

To keep up to date with my latest blog posts, you can like my Facebook page, or follow me on Twitter. You can find them by clicking the relevant icons in the sidebar.

Next week I will be looking into the intriguing tale of Matthias Buchinger, the deformed entertainer.

The Wheelchair Historian

Further Reading

Brignell, Victoria, ‘Ancient world’, 7 April 2008 https://www.newstatesman.com/blogs/crips-column/2008/04/disabled-slaves-child-roman Accessed: 9th October, 2020.

Facts and Details, ‘Slaves In Ancient Rome: Numbers, Sources And Laws’, Last updated October 2018 http://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub369/entry-6302.html Accessed: 9th October, 2020.

Garland, Robert, 1995. The Eye of the Beholder: Deformity and Disability in the Graeco-Roman World (London).

Lampridius, Aelius, Historia Augusta, Commodus. Translated by David Magie (January 1921), 7.11.2.

Lucian, The Carousal (Symposium) or The Lapiths Translated by A. M. Harmon (January 1913), 18.

Malamud, Martha, “That’s Entertainment! Dining With Domitian in the Silvae.” Ramus 30.1 (2001), 23-45.

Plutarch, ‘On Being a Busybody’ in Moralia, Volume VI Translated by W. C. Helmbold (January 1939), 520 C p. 501.

Quintilian, ‘The Orator’s Education’ in The Orator's Education, Volume I: Books 1-2, edited and translated by Donald A. Russell (January 2002) 2.5. 11-12.

Spectacular Antiquity, ‘Dwarfs in the Roman Arena’, https://spectacularantiquity.wordpress.com/case-studies/public/dwarfs-in-the-arena/ Accessed: 9th October 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment