Welcome to my latest post in my series on disability as entertainment. This week I will be looking at the German performer, Matthias Buchinger.

Who was he?

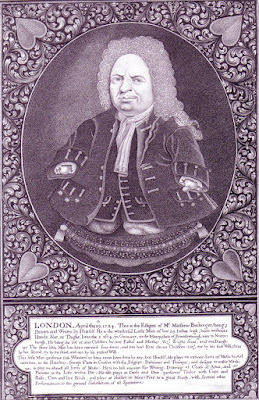

Matthias Buchinger (1674-1740), was a man of many talents. He was a performer, artist, musician, and calligrapher. Born in Ansbach, Germany, his parents tried to keep him hidden. The reason for this was that he was born without arms, legs, or thighs and was only 29 inches tall. It is believed he had phocomelia, which causes arms and legs to malform. Buchinger decided to head out onto the streets to perform, starting in Germany, but he became popular right across Europe. He travelled to many countries including France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Britain, and Ireland. He even performed for various royal families. He was a very active man, marrying a Dane as the first of his four wives. He is also known to have produced fourteen children by numerous women. Several dozen women claimed to have carried his child, but none of these claims can be substantiated. Buchinger even had a poem published in an English broadside entitled “A Poem on Mathew Buckinger: The Greatest German Living” in 1726. The Greatest German Living is a rather impressive compliment!

In 1714, George, Elector of Hanover, became George I of Great Britain. As the new king was German, Buchinger felt that he would fit in rather nicely at court and would gain the favour of George I. However, this was not the case. Instead, the king simply paid Buchinger twenty guineas to leave him alone. Buchinger was therefore left with no option but to continue displaying himself in public and headed to Ireland. He performed in Dublin, Belfast, and Cork. He died in Cork in 1739, but insisted that his friend from Dublin, Francis Smith, acquire his body to prevent it from being put on display as a curiosity.

What were his Abilities?

Ok. So, he was a disabled performer who was popular in many European countries, but what did his acts entail? What could a man with no hands or feet possibly do to captivate an audience? Well, it turns out that he could do quite a few things. He was quite good at magic for instance. In Temple Bar, Dublin, in 1720, he performed cup and ball tricks. A Trinity College student commented that ‘From what was but a lifeless ball before, at his command, a living bird will soar.’ I must confess that I know very little about magic. I assume that slight of hand tricks are difficult to pull off, even more so when you don’t actually have hands! I wonder when they were referring to Buchinger, was it slight of stump.

It was not just his arms that he was quick at moving. Another onlooker stated that ‘He twists himself about the floor with considerable agility, raising one side a little & turning on the other as on a pivot.’ It is clear that Buchinger could do amazing things with his body. He could also perform a trick involving nine pin bowling. He would place a glass of liquid on top of a skittle and knock the skittle over without spilling any of the liquid. He also could play several different musical instruments. If you think that is impressive, wait until you hear this. He was able to load and fire a gun. That’s right! The man without any hands was able to load and fire a lethal weapon. I think it is fair to say that his impairments did not hinder his performances.

|

| The Lord's Prayer engraved in Buchinger's wig |

Calligraphy

I have decided to leave Matthias Buchinger best skill till last. You see, he was amazing at calligraphy, particularly micrography. Possibly the best example of this is a self-portrait of his (shown above). The drawing itself is pretty good, but it is only when you look closely at his wig that you realise how skillful he truly was. The curls of the wig are actually words and when they are strung together, they make up seven complete psalms and the Lord’s Prayer. He used the same micrography skills while working on a portrait of Queen Anne, as well as a family tree. Nobody has been able to work out how he achieved this feat. Not only because he had just a thumb-like nob on one arm to work with, but witnesses state that he never used a magnifying glass in the process. This boggles the mind, as the writing is so small, most people require a magnifying glass to read it.

Matthias Buchinger came back into the public’s imagination in 2016, when the New York Metropolitan Museum ran the exhibition ‘Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger's Drawings from the Collection of Ricky Jay’. Ricky Jay was an excellent slight of hand magician and actor. He had spent time studying Buchinger and published the book Matthias Buchinger - 'The Greatest German Living' in 2016.

Matthias Buchinger was an incredibly talented man,

regardless of his disability. If you want to learn more about him, I highly recommend the BBC podcast episode listed in the Further Reading below.

To keep up to date with my latest blog posts, you can like my Facebook page, or follow me on Twitter. You can find them by clicking the relevant icons in the sidebar.

Next week, I will start to delve into the world of the freak show.

The Wheelchair Historian

Further Reading

BBC, Disability: A New History, Episode 3: Freaks and Entrepreneurs, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b01smkq3 Accessed: 16 October 2020.

Bunbury, Turtle, ‘MATTHIAS BUCHINGER (1674-1739) – THE GREATEST GERMAN LIVING’ http://www.turtlebunbury.com/history/history_heroes/hist_hero_buchinger.html Accessed: 16 October 2020.

Jay, Ricky, ‘Desperately Seeking Susan’, June 1, 2009 https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/02/opinion/02jay.html Accessed: 16 October 2020.

Johnson, Ken, "Astounding Feats in Pen, Ink and Magnifying Glass" The New York Times (January 14, 2016). https://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/15/arts/design/astounding-feats-in-pen-ink-and-magnifying-glass.html Accessed: 16 October 2020.

Library Ireland, ‘Matthew Buckinger’, from the Dublin Penny Journal, Volume 1, Number 44, April 27, 1833, https://www.libraryireland.com/articles/BuchingerDPJ1-44/index.php Accessed: 16 October 2020.

Mittman, Asa Simon, ‘Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger's Drawings from the Collection of Ricky Jay’ (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 8 January-11 April 2016). Exhibition publication Ricky Jay, Matthias Buchinger: ‘The Greatest German Living’. Los Angeles: Siglio, 2016.

Sadlier, Thomas Ulick: ‘An eighteenth century dwarf’. Journal of the County Kildare Archaeological Society, v.X (1922-8), p.49-60, http://archive.irishnewsarchive.com/olive/apa/KCL.Edu/#panel=document Accessed: 16 October 2020.

Schjeldahl, Peter, ‘Seeing and Believing: the mysteries of Matthias Buchinger’, The New Yorker, January 18, 2016 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/01/25/seeing-and-believing-the-art-world-peter-schjhl Accessed: 16 October 2020.